The FBI finally gave up.

After chasing thousands of leads over more than four decades, the federal law-enforcement agency closed its D.B. Cooper case in 2016 without a resolution. Whoever boarded Northwest Orient Flight 305 in Portland on Nov. 24, 1971 — and then parachuted out of the Boeing 727 hours later with $200,000 in ransom — had stumped the feds once and for all time.

The FBI may have assumed its decision would quickly drop from the news cycle and that public interest in the long-ago skyjacker would fall away for good. After all, D.B. Cooper’s heyday had been way back in the late 1970s, when novelty songs and even a fictional Hollywood movie embraced the unknown criminal as a folk hero.

But when the bureau walked away from the only unsolved skyjacking in U.S. history, longtime D.B. Cooper aficionados became determined to push the subject back into the spotlight. This loose collection of amateur investigators, who had flown under the pop-culture radar for years, believed they could succeed where the professionals had failed.

And they have made progress. New books and documentaries about the case — with new revelations — have hit the market in the last couple of years. CooperCon 2021, featuring a packed roster of experts to mark the skyjacking’s 50th anniversary, will take place Nov. 19-21 in Vancouver.

Does that mean a definitive break in the case is on the horizon? Or that it’s only bogging down ever deeper in the evidentiary muck?

The FBI over the years essentially ruled out a lot of suspects, including some high-profile ones, such as Richard Floyd McCoy, Kenneth Christiansen, Robert Rackstraw and Duane Weber.

But with the feds abandoning the chase, believers in these suspects redoubled their efforts, sometimes leading to clashes.

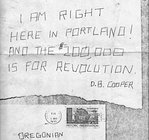

When TV producer Thomas Colbert announced in 2018 that a former Army codebreaker he’d recruited had cracked a cipher in an old letter purportedly from the skyjacker — and that this proved Rackstraw was Cooper — Weber’s widow reacted with fury. Jo Weber sent a series of emails to The Oregonian/OregonLive, in which she claimed she had found the cipher in her late husband’s address book years before it was publicly revealed.

“Colbert and Rackstraw had nothing to do with the Code — I had the code years ago,” Jo Weber wrote. “That code was used by me years ago — with information on Weber I sent to the media, but no one got it but me.”

In the end, the cipher wasn’t the breakthrough that either Colbert or Weber thought it was.

Cryptology experts told The Oregonian/OregonLive that the method Colbert’s codebreaker used was fatally flawed. One of the cryptologists said it had “no value in determining reality.”

Which didn’t put an end to anything, of course.

New Cooper-case obsessives started coming up with new suspects — possible D.B. Coopers the FBI apparently never discovered.

One of those obsessives, New Hampshire engineer Bill Rollins, believes that a late military man named Joseph S. Lakich must have been the carefully groomed man who, using the name “Dan Cooper,” paid $20 in cash for a ticket on Flight 305.

“I no longer say I think it’s Joe Lakich,” Rollins recently said. “I say, emphatically, it’s Joe Lakich.”

He reached this conclusion after spending months scouring databases, using the bits and bobs known about the skyjacker to create his own, very long suspect list — and then culling it, one by one.

“I just kept going and going until I found Joe, and I couldn’t eliminate him,” he says.

Rollins’ theory: Lakich, a Nashville resident at the time, wanted to make the FBI look bad after the bureau had bungled its response to a 1971 Florida hostage-taking that caused his daughter’s death. Rollins admits that, all these years later, he feels some satisfaction on Lakich’s behalf.

“Joe Lakich spanked the FBI!” he exults.

Another new suspect has come from a U.S. Army officer, who prefers to keep his name out of the public sphere because of his day job in Washington, D.C. — though he will make an appearance, sans anonymity, at CooperCon this month. Like Rollins, the officer used public-records databases that have become widely available since the arrival of the internet.

The key clue in his search: In 1972, a mysterious person claiming to be D.B. Cooper sent a letter to the journalist Max Gunther. The letter writer told Gunther that, if he wanted to hear the real story about the skyjacking, he should place a classified ad in the Village Voice on March 2nd saying “Happy Birthday Clara.” Gunther did so, but his new correspondent didn’t follow up.

Decades later, the Army officer believes he figured out who Clara was, ultimately leading him to conclude that Cooper was a New Jersey man named William J. Smith, who died in 2018.

These new theories are fascinating, tantalizing, but they remain far from definitive.

During the past couple of years, broadcaster Darren Schaefer has talked to a range of forensics experts, law-enforcement veterans and general true-crime addicts for his podcast The Cooper Vortex. Neither Lakich nor Smith is at the top of his list.

“If I absolutely had to pick a suspect, I’d go with Wolfgang Gossett or Ted Braden, but I’m not sure of either,” Schaefer told The Oregonian/OregonLive.

Wolfgang Gossett? Ted Braden?

Like Lakich and Smith, these are low-wattage stars in the D.B. Cooper firmament, unknown to casual followers of the case. (Braden was a Vietnam War veteran, later a mercenary and maybe a CIA operative. Gossett had an eclectic career that ranged from Army paratrooper to priest.)

Eric Ulis, the organizer of CooperCon and one of the highest profile Cooper hunters, spent years trying to prove that a World War II veteran and 1950s smokejumper named Sheridan Peterson was the skyjacker. He burrowed deep into Peterson’s life, including interviewing his suspect. Peterson died earlier this year at 94.

But Ulis recently abandoned his belief in Peterson, chiefly because of one small personal detail. He couldn’t locate a speck of evidence that the man had ever smoked cigarettes. Not even occasionally. Not even in his youth.

The man who hijacked Northwest Orient Flight 305 smoked relentlessly on Nov. 24, 1971.

“If he was faking it, that would be a lot,” Ulis told The Oregonian/OregonLive. “He’d be sick. I had no choice but to eliminate him as a suspect.”

He now assumes that none of the suspects identified by the FBI or debated over the years on D.B. Cooper internet forums is the skyjacker.

“Honestly, I believe it’s a guy who’s a complete unknown,” he says. “I’ve seen nobody who checks all the boxes. It’s somebody who’s flown under the radar for 50 years.”

Ralph Himmelsbach, the first FBI agent in charge of the Cooper case, didn’t think much of hobbyists like Rollins and Ulis. The veteran agent, who died in 2019, became convinced early on that the skyjacker was incompetent and almost certainly perished on the night of the crime. He explained why he thought so in the mid-1970s.

“He cut the shroud lines on one of the best parachutes [he was given] and used them to tie the 10,000 $20 bills to his belt in a bag before he bailed out,” Himmelsbach told The Oregonian.

He said the skyjacker “left behind the two best parachutes — a sky-diver parachute with a 32-foot canopy and a chest pack designed primarily for use as a second parachute.” Cooper took instead a pilot’s “seat-back parachute” and a training parachute that was unusable.

“No one who knew anything about parachutes would have made this many mistakes,” he said.

He also dismissed the theory that the skyjacker’s instructions to the pilot, which allowed the plane to fly safely with the aft stairs deployed, meant he had special knowledge that was then known only to a few Boeing and military officials.

Himmelsbach added that on the stormy, pitch-black night of the skyjacking, Cooper would have had no idea where he was when he leapt from the plane’s back stairway, rejecting the popular theory that he had confederates on the ground helping with the getaway.

The skyjacker would have hit the ground at a speed of at least 50 miles an hour, all but ensuring injury of some sort, and quite possibly a fatal one, Himmelsbach said.

And if “Dan Cooper” did somehow land safely?

The trek through dense forest on a frigid, rainy night would have been rough going. Himmelsbach noted that the skyjacker was dressed in a dark suit and business shoes on the plane, and that he didn’t have goggles.

“Parachute experts tell us his shoes would have been snapped off his feet when he stepped out into a 196-mile-an-hour slipstream,” the FBI agent continued in the 1976 interview. “His eyes would have been blacked by the force of the wind and he probably would have tumbled out of control.”

More than 40 years later, in his last interview on the subject, Himmelsbach told The Oregonian/OregonLive that his opinion hadn’t changed. Nov. 24, 1971, he said, was most likely the skyjacker’s last day alive.

In January 1972, a Himmelsbach-led team attempted to re-enact Flight 305′s journey from Seattle, where the plane had taken on the ransom money, to Reno. A Boeing 727 flew over the same route, at the same speed and elevation and with the same load. The flight even included William Rataczak, who had been Flight 305′s first officer, in the cockpit.

The reenactors lowered the rear stairs in flight, just as the hijacker had. At about the same point that Cooper likely jumped — based on a brief, thudding change in cabin air pressure on Flight 305 — they dropped out a “sled” and tracked its parachute-guided trajectory to the ground. The feds came up with an area of about 7 miles by 4 miles near Lake Merwin in Washington state where the skyjacker would have landed.

Then they sent some 200 law-enforcement officers and National Guard soldiers into the “jump zone” to search for evidence. They found a few old weather balloons and the body of a murder victim, but nothing that had anything to do with the hijacking of the Northwest Orient flight.

“It is impossible to conduct a 100% effective search in some of this area,” Himmelsbach said at the time. “There are acres and acres of blackberries so dense as to be impenetrable, and some of the terrain is too steep to be searched on foot. A man could fall into one of those blackberry patches and just disappear.”

To be sure, there are hints that D.B. Cooper might have survived.

A couple of people were out driving in the jump zone on the night of the skyjacking and said they saw someone walking along the side of a remote forest road. A 1972 FBI field report stated that one witness “recalled that at the time she thought the man appeared strange because, although the weather conditions were poor, the individual was wearing only a dress-type, white shirt and dark slacks.”

Over the years, many independent Cooper investigators have taken issue with the FBI’s search area, insisting it was too small, or, worse, based on faulty flight-path data.

And then there are the theories and investigative possibilities that opened up in 1980 when $5,800 from the ransom haul was found along the Columbia River on a private beach known as Tena Bar.

Did D.B. Cooper bury the money there on the night of the skyjacking — or years later? Did the three bundles of cash float down the river to the beach? Were they tossed onto it during a 1974 dredging operation?

Darren Schaefer, like so many people before him, has tried to get to the bottom of all the theories and evidence — in his case not by becoming an investigator himself but by inviting D.B. Cooper experts onto his podcast and hearing them out.

But he admits that, even after 52 episodes, he has “no idea who D.B. Cooper was. To quote Albert Einstein, the more I learn the more I realize how much I don’t know.”