. The ferry could carry a four-horse team and wagon, or two city of Centralia 1.jpg)

I started digging into the history of the Elkanah Mills family after receiving an email from Greg Isaacson, of Chehalis, who expressed concern about the deterioration of the Borst blockhouse, a historic landmark nestled among the trees of Fort Borst Park in Centralia.

More than three years ago, he expressed similar concerns in an April 4, 2019, letter to the editor headlined “Fort Borst Park Blockhouse Deserves More.” He urged city officials to consider relocating the blockhouse, which was described in 1941’s “Centralia: The First Fifty Years, 1845–1900” as “one of the best-preserved landmarks of the pioneer life in Washington.” He said it belongs near the Borst home, where it sat during the 19th century, near the replicated one-room school and pioneer church.

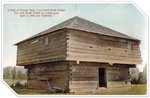

During the Indian Wars of 1855–56, Captain Francis Goff, in charge of 26 Oregon Volunteers, with help from local pioneers — Joseph Borst, Patterson Luark, and James Lum — constructed the blockhouse in the spring of 1856 at the junction of the Chehalis and Skookumchuck rivers. They used axes to cut, peel, hew and score the logs, closely fitting the dove-tail corners and sides to form the blockhouse, which originally had only one door and no windows but nearly two dozen narrow loopholes for shooting through. The blockhouse never protected pioneers, but rather stored grain brought downriver from Claquato.

When the war ended, Borst bought the blockhouse from the U.S. government for $500 and, in 1857, lived in it with his wife and family while renting his home to James Smith. He added windows and an upper level door at that time. Joseph and Mary Borst’s second child, Ada, was born in the blockhouse, which later became a playhouse for their children. In the early 1860s, the Borsts once again moved into the blockhouse while constructing the white house with green shutters that Joseph had promised his bride.

When the Chehalis River altered its course in 1915, it threatened the blockhouse. So, in 1919, it was jacked up on skids and rollers and moved to what is now Rotary Riverside Park. Then, in 1922, it was moved to its present location in Borst Park. The following year, Joseph and Mary’s youngest son, Allen, presented it to the City of Centralia.

Through the decades, the blockhouse has received repairs such as a building a foundation, replacing rotted timbers, and adding a new roof, but time and the elements continue to take a toll on this historic landmark. Unlike the Borst home, the blockhouse is not listed on the National Historic Register, but it still warrants preservation.

A decade ago, the Centralia Historic Preservation Commission urged the city to move the blockhouse from its damp and dark location to its original spot near the Borst House along the Chehalis River.

Roy Matson, vice chair of the commission, said in June 2012 that the blockhouse “needs more light and a drier location.” He said the group planned to identify necessary repairs, find a new site, and move it.

“I’m fine with its location,” Community Development Director Emil Pierson, who oversees the city’s parks, said at the time, adding that he also supports the Historic Preservation Commission.

In 2014, Matson and city officials contacted Harrison Goodall, a historic preservation specialist with Conservation Services LLC in Langley, Washington, to examine the blockhouse and develop a detailed preservation plan, which he presented in May 2016. His report can be found at https://www.cityofcentralia.com/272/Fort-Borst-Restoration.

“Considering the environment and fragility of a log structure, it is in relatively good condition but needing preservation attention,” Goodall reported.

After outlining what needed to be done, he concluded finding a contractor skilled in hewing square logs, maintaining historic accuracy and matching workmanship might prove challenging.

“The unknown for me is the plans for moving the structure,” he wrote. “Obviously, my recommendations are for the structure staying in place.”

He cited concerns about drainage and the roof structure stabilization in moving a log building.

“Only a few blockhouses remain in Washington,” he said. “From my perspective, I feel it extremely important, and an obligation, to preserve these treasures for people in the future. They are unique and they tell a visual story about early life here in Washington. Retaining their integrity and character are paramount.”

I couldn’t agree more.

The city accepts donations to “Save the Borst Blockhouse” at Centralia Parks Department, P.O. Box 609, Centralia, WA, 98531, Attn: Borst Blockhouse Restoration.

Peter Lahmann, president of the Lewis County Historical Society, has been working with city officials to coordinate volunteer restoration efforts.

Another historic preservation problem is deterioration of the inscription panels on the Sentinel statue in Washington Park in Centralia.

IWW Plaque on Agenda

The Sentinel statue has stood in Washington Park since 1924 to honor four World War I soldiers killed during the first Armistice Day parade Nov. 11, 1919. For years, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) has tried to place a separate bronze plaque in the park as a memorial to union workers killed or imprisoned as a result of the Centralia Tragedy (also known as the Centralia massacre).

The Centralia City Council will review Mike Garrison’s proposal at a 7 p.m. meeting Oct. 11. The IWW plaque has been reviewed by the city’s Parks Board, which in a 3-0 vote issued a draft recommendation to support the monument, “but would like to have the wording more factual, more neutral, no logo and more historically detailed.” Those caveats raise a lot of questions and potential for problems.

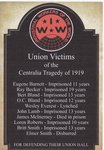

Mike Garrison, an IWW member, proposed a bronze plaque bearing the IWW logo at the top followed by the words: “Union Victims of the Centralia Tragedy of 1919.” It then lists the names of those men: Eugene Barnett — Imprisoned 11 years; Ray Becker — Imprisoned 19 years; Bert Bland — Imprisoned 13 years; O.C. Bland — Imprisoned 12 years; Wesley Everest — Lynched; John Lamb — Imprisoned 13 years; James McInerney — Died in prison; Loren Roberts — Imprisoned 10 years; Britt Smith — Imprisoned 13 years; and Elmer Smith — Disbarred. Beneath their names, it says, “For Defending Their Union Hall.”

I’ve never had a problem with the IWW’s proposed plaque as a counterweight to the American Legion’s Sentinel statue. With the IWW logo, it clearly states this is the union’s perspective.

My problem in 2019 as part of a committee reviewing options was the attempt to cast in stone — literally — one narrative of events when the sequence of what transpired that fateful day has been debated for decades: Did someone fire first at the soldiers in the parade who then rushed the IWW hall? Or did soldiers in the parade attack the union hall before gunfire erupted?

Three years ago, when Garrison proposed the IWW plaque, Jay Hupp, a Centralia High School graduate from Shelton, and others wanted to write a narrative — without any attribution — stating that soldiers attacked the union hall first and then gunshots rang out.

A century later, without proof, they wanted to write a narrative that condemns the four soldiers shot to death in Centralia — not inside the IWW hall — and blames them for their deaths.

It may have happened that way. But it might not have. A jury didn’t believe events occurred the way Hupp stated in his proposed narrative.

We do know a mob broke into the city jail, hauled out Wesley Everest, and lynched him from what was known for years as Hangman’s Bridge over the Chehalis River at Mellen Street. Nobody was ever convicted in his death.

Garrison’s proposal seeks to honor Everest and those who were convicted and sentenced harshly at a time when anti-union sentiment ran high. He asks for “historical balance” because the Sentinel states the Legionnaires were “slain while on peaceful parade,” while the IWW plaque would state that the union victims were “defending their Union Hall.”

Garrison’s plaque, with the IWW logo, provides the union counterbalance to the Legion’s Sentinel statue and honors Everest, attorney Elmer Smith, and those union men who were incarcerated after the clash.

A narrative that states without attribution that events unfolded one way or the other would be just plain wrong.

Julie McDonald, a personal historian from Toledo, may be reached at memoirs@chaptersoflife.com.