, brother Gosse, and mother Atje Van Wyngaarden Klijnsma before the youngest girl was born.jpeg)

at 18.jpeg)

As a young teenager, Grietje Klijnsma stood on a Heerenveen street in the northern part of The Netherlands and watched an Allied pilot eject from his airplane, but as he was dangling from his parachute, floating toward the ground, German soldiers shot off his legs.

The horrific violence haunted her — and still gives her nightmares eight decades later.

As I interviewed Grace Andree at her Centralia home last week, I thought of all those Ukrainian children who today are living through the horrors of war, who more than likely will suffer nightmares decades later — if they live that long.

Grietje, today known as Grace, celebrated her 94th birthday Wednesday. She was only 11 when she climbed a ladder to reach a high point on a gate and watched German soldiers with tanks invade her homeland in May 1940.

When the Nazis invaded, what had been an idyllic childhood in Heerenveen, a horse-and-buggy town founded in 1551 in the province of Friesland, changed overnight.

“We were very spoiled,” she said.

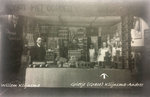

Her grandfather, Gosse Klijnsma, had started a grocery store on a busy street in the town in 1910. Thirteen years later, her father, Willem, took it over and operated it until 1985.

But he didn’t sell groceries to the Nazis.

“They stole it,” Grace said. “They took what they wanted.”

As a grocer, her father could trade items like coffee, tea, klompen (wooden shoes), halters and rope for meat. The Germans claimed ownership of all animals, but farmers would butcher a newborn calf to eat and sell before the Nazis could count it. The family — Willem and his wife, Atje, a son, Gosse, and two daughters, Greitja (Grace) and Jannie — never experienced hunger as some did in Holland, surviving on tulip bulbs, but they witnessed atrocities and tread softly.

Grace recalled one man, a member of the underground, who dove into a river to escape capture by Nazi soldiers. Her father knew people in the Dutch Resistance. Nobody spoke about it, but her father was patriotic and likely supported the underground. They kept a radio hidden in their home.

The war years proved traumatic for the entire family.

In August 1942, her 18-year-old brother, who attended secondary school and helped his parents at the grocery store, suddenly collapsed in pain and died from twisted intestines.

So at the age of 14, Grace quit school to work in the store, serving as a clerk, weighing produce and other goods to sell to customers. The horses she grew up seeing on the streets — including neighbor kids flying through town on horseback — gradually gave way to cars.

On the last day of the war, as the Germans retreated, blowing up bridges and destroying munitions they couldn’t carry with them, they ordered everyone to stay inside their homes.

“So of course, nosy me, I had to go out,” she said. “I came very close to being shot.”

Soldiers ordered her back inside. Down the street, she saw the bodies of her neighbor and his teenage son, shot dead.

After the American soldiers arrived, Grace’s good friend told her never to call her by her first name around them. Her friend was Frockya Ani.

One time, when Grace was crossing a plaza from the railroad station, where the Red Cross had set up tents, an American soldier beckoned to her.

“He said, ‘Come here’ to me,” she recalled. “We trusted the Americans totally — those were our friends.”

She followed him inside a tent. He opened a can of peaches and he said, “This is for you.”

“I ate the whole can of peaches,” she said. “We hadn’t had that for many years, you know. And then he gave me a can and he said, ‘This is for your mother.’”

After the war, they opened their attic to refugees, but they had no plumbing up there, so they used buckets as a toilet. One refugee was a teenage boy.

“That’s the one that I remember because he filled up that bucket,” Grace said. “My father had to empty it and he carried it so careful so not to spill.”

He wouldn’t have trusted the teen with carrying the bucket.

The first time she used a telephone, her friend Frockya Ani showed her how to use it at a hotel and restaurant. Grace dialed the number and started yelling on the phone. “I never called again,” she said. “I was too nervous.”

As a teenager, Grace dated. What did they do on dates?

“Kissy, kissy,” she responded.

Her answer prompted laughter among her two daughters — Audrey Birdwell and Margaret Blankenship, both of Centralia — and her granddaughter, Mary Andree of Rochester, and friend Edna Fund, who had brought Pastor Frank Corbin for a visit the previous day. He had known Grace and her husband, Peter, when they ran a dairy farm on Puget Island in Wahkiakum County. As he left, he asked if he could kiss her on the forehead. “You can kiss me wherever you like,” she told him.

She and a boyfriend dated for three years, walking hand in hand, sailing on his boat and enjoying life after a siege of war. But after he joined the military and left for Indonesia, Grace married her next-door neighbor, Pieter Andree. She’d known him since they were both children, she said, “but he wasn’t my type.”

I’ll continue Grace’s story next week.

•••

Julie McDonald, a personal historian from Toledo, may be reached at memoirs@chaptersoflife.com.