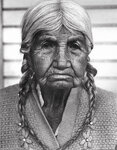

, famed Cowlitz basket weaver, n.d.. Courtesy United States Forest Service.jpg)

Jan. 3 marks a birthday celebration, the date when a well-known Upper Cowlitz woman was born beside the banks of the Cowlitz River near present-day Randle about 170 years ago.

Official Yakama records say Mary (Yoke) Kiona was born at Silver Brook on Jan. 3, 1855, although other accounts say Mary, a member of the Tai’t-na-pam tribe, was born in 1849, 1852 or 1853. Her father, William Yoke, was a Yakama native who married Lucy, a member of the Cowlitz Tribe.

Whatever the year of her birth, Mary was old enough to remember lying on a hill and watching the first white people in covered wagons travel into the valley. Her uncle, Jim Yoke, described them as “ghosts with beards.” She lived to be 107, 115, 117 or 121 and provided a historic link to early life in East Lewis County. She remembered the bountiful days before white settlers arrived when only four Indian families lived nearby.

At 16, she married Charley Kiona, and together they had several children, including a son, Jim, who served in the military during World War I, and daughters Minnie Placid and Ora Woods. Her husband died in 1908, and she remained a widow for more than six decades.

Mary learned at an early age to craft baskets from spruce roots and strapped a basket onto the top of her head to carry what she gathered. She was known for daily 10-mile walks to visit friends and relatives. In her 90s and later, she would hitch up eight to 10 horses in a pack train and head into the mountains to dig roots, pick huckleberries, and gather grasses for her basket weaving. She took a “half-squirrel-half-fish” totem with her.

The Tai’t-na-pam, estimated to number more than a thousand at one time, used to deliberately burn land to help promote the growth of blackberries and, at higher altitudes, huckleberries.

Mary said her uncle was the first to discover the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. She recalled generations of natives bathing in soda springs near Mount Tahoma “until whites fenced it off and charged an entry fee.”

George Blomdahl, a longtime Daily Chronicle reporter, interviewed Mary Kiona in January 1970 when she celebrated her 115th birthday. Her granddaughter, Joyce Eyle, of Silver Creek, interpreted her grandmother’s soft spoken native tongue into English. The Upper Cowlitz communicated in Salish or the Yakama’s Sahaptin language. The Lewis County Historical Museum has a December 1969 recording of Mary answering questions with Eyle interpreting.

Mary told Blomdahl of monthlong family campouts at Packwood each October when her relatives gathered to hunt, fish and pick huckleberries. They ate bread, salmon and barbecued venison. Sometimes, Yakama natives joined them. The Upper Cowlitz and the Yakamas met every year in the shadow of Mount Tahoma, “The Mountain That Was God,” now known as Mount Rainier.

Mary also spoke of a Cowlitz flood in the late 1800s that swept away everything. She said a neighbor found his bull in a tree, still alive and bellowing at the top of his lungs. She also predicted a “big water” would thunder out of the hills and roll over the dams on the Cowlitz River.

In her 1969 interview, Mary said the Yakama and Cowlitz often fought. The Yakama took everything they could, even a cradle, she said, but they wouldn’t lay a compass on their property — or take their land. She said the Cowlitz never enslaved anyone and respected the rights of others.

During the interview, she spoke about meeting a blue-eyed French-Canadian trapper, Pierre Charles, near Mary’s Corner south of Chehalis. She also talked about rainy weather and floods.

The Chehalis got along with the Cowlitz, she said, but they didn’t intermarry. At the end of the recorded interview, she mentioned that she liked her country, sang an old Cowlitz song, and noted she could have been a doctor.

When she died in June 1970, the news spread across the nation, with her obituary appearing in the San Francisco Chronicle in California, the Hartford Courant in Connecticut, the Tyler Morning Telegraph in Texas, and the Palm Beach Post in Florida.

Not bad for a Tai’t-na-pam woman who lived all her life in East Lewis County.

Mary’s legacy lives on in Lewis County. Kiona Creek was named for her family. The Kiona Cemetery west of Randle, on property where Mary Kiona once lived, was the final resting place of 16 Kiona family members, including Mary’s daughter, Ora. However, Mary was buried near Oakville.

A mural of Mary Kiona graces a Packwood market. Outside White Pass Country Museum stands a cedar story pole with a snow goose on top, which represents Mary; a salmon memorializing her uncle, who provided fish to settlers; and a beaded bag for his wife.

The Mary Kiona Foundation helps people suffering from homelessness address physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

I researched the history of Mary Kiona and other Native American women last summer for an hour-long presentation at the St. Helens Club in September, where our theme for the year is Washington Women of Influence.

Mary Kiona was a niece of Cowlitz Chief Anton Scanewa and cousin to Thas-e-muth, the first wife of Simon Bonaparte Plamondon, who settled in the Toledo area in the early 1820s.

Thas-e-muth was one of three daughters and three sons born to Chief Scanewa and his wife, Ta Wis Na. The chief, who was said to have seven wives among different tribes in Western Washington, oversaw 17 subchiefs and their tribes from the Columbia River north to the Fraser River in present-day British Columbia, according to Roy I. Rochon Wilson, of Winlock, who served the Cowlitz tribe for three decades and wrote dozens of books, including tribal histories.

Although the tribe historically lived along the Cowlitz and Lewis Rivers, Thas-e-muth was born at Fort Langley in British Columbia in 1800.

The Cowlitz first met “the Astorians,” white fur trappers from the Pacific Fur Company, during a peaceful encounter in 1811. But a few years later, violence erupted when the North West Company sent trappers into Cowlitz lands, accompanied by Iroquois Indians who assaulted several Cowlitz women. Warriors killed one of the Iroquois and wounded two others, but in retaliation, the Iroquois attacked a Cowlitz village and killed about a dozen people.

Thas-e-muth was a teenager in 1818 when men in a canoe paddled up the Cowlitz River to her village near present-day Toledo. As soon as the explorers with the Hudson’s Bay Company pulled up to the riverbank, they were captured and imprisoned by Lower Cowlitz warriors who took them to Chief Scanewa.

Among the prisoners was a lanky young man named Simon Bonaparte Plamondon Sr., who had been asked to explore the country to find good places for fishing, trapping and farming. He was born on April 1, 1800, in Sorel, Quebec, on the St. Lawrence River northeast of Montreal. His parents drowned when he was 10. At 13, he accompanied his older brother to Astoria, and at 16, he started working for the North West Company, later absorbed by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Simon gained the tribe’s trust by staying with them and trapping animals for their fur. In 1821, Scanewa, the strong Lower Cowlitz chief who stood over 6 feet tall, arranged for Plamondon to marry his daughter, Thas-e-muth. The chief performed the Cowlitz Sun Rites among a grove of trees on the Cowlitz River’s north bank, according to The Plamondon Family by George Francis Plamondon. The chief also gifted Simon with twenty braves to call his own.

When a priest visited the village, Thas-e-muth was baptized and given the name Veronica. She gave birth to four children — Simon Bonaparte “Bony” Jr., and daughters Marie-Anne, Sophie, and Therese — before her death on April 7, 1834, when she was in her mid-30s.

During a visit to Fort Langley in 1827, Chief Scanewa gambled and won, leaving other players disgruntled. He stayed an extra night at the fort, but on his way home with a young wife and year-old daughter, he was robbed and murdered by Klallam Indians, Wilson wrote. His wife and daughter were taken prisoner, although the perpetrators were later captured, tried and convicted at Fort Langley.

Upon Chief Scanewa’s death, Simon Plamondon Sr., who continued to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company, inherited most of the chief’s property and, because the chief’s eldest son was too young to lead the tribe, he became the Cowlitz leader until Richard “Tyee Dick” Scanewa was grown. Another of Scanewa’s sons, Antoine, later became chief.

Thas-e-muth’s story always fascinated me because I wondered whether she had a choice in marrying Simon Plamondon or if she had been given to him as her father had gifted the braves as a wedding present. Was she honored to marry this 6-foot-2 white man? Or would she have preferred a Cowlitz husband? We’ll never know for certain.

Her youngest child, Therese, married “Elie” Sareault and their son, John Sareault, later became the Cowlitz tribe’s chief.

Simon helped establish the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 5,000-acre Cowlitz Farm near Toledo in 1838, later called the Puget Sound Agricultural Company. He served in Oregon Territory’s Provisional Legislature, attended the Cowlitz Convention in 1852, and petitioned for a separate territory north of the Columbia River, which happened with the creation of Washington Territory in 1853. He built the first brick kiln in the state and erected a sawmill in 1847.

After Thas-e-muth’s death, according to his descendant Michael Hubbs, Simon Sr. married Emelie Marie (Finlay) Bercier, the French-Canadian widow of Pierre Bercier who disappeared in the early 1830s. Simon fathered five more children with her. They moved to a home on the Cowlitz Prairie — along a road that today bears his name — above what became known as Cowlitz Landing on the nearby river. A year after Emelie died in 1847, possibly during a measles outbreak, Simon married Louise Henriette Pillifier, the niece of Archbishop Francis Norbert Blanchet and Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet, and fathered two more children. He also fathered a child with Kitty Tilikish, his common-law wife. Altogether, he had four wives and fathered at least a dozen children before he died at nearly 100.

He was buried at the St. Francis Xavier Mission cemetery near Toledo.

Next week I’ll share more about Native American women of influence in Washington state.

•••

Julie McDonald, a personal historian from Toledo, may be reached at memoirs@chaptersoflife.com.