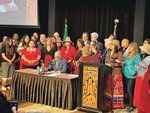

In March, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed a bill into law that would create a statewide alert system for missing Indigenous people. It was the first of its kind to be put in place across the nation.

Nisqually Tribal Council member Chaynannah Squally was in attendance at the singing event at the Tulalip Tribe’s Resort Casino. Squally said the event was beautiful and marked one of her first big events as a councilwoman for the tribe.

“After the bill was signed and Gov. Inslee and his team had left, I was wrapped with a blanket and sat and watched the ceremony take place,” Squally said. “I was asked to speak, which I was very nervous about, so I spoke in my ancestral language because not only was I speaking to the people there, I was speaking to our ancestors. This is a huge moment for us all.”

The system created is like an Amber Alert, which is used to notify the public when a child or vulnerable adult is reported missing. It will also notify law enforcement when there is a report of a missing Indigenous person. An alert will appear on highway reader boards, on the radio and on social media. Media organizations will also be presented with information on the alerts.

The law expands the definition of “missing endangered person” to include Indigenous people.

“This system will help us jump the divide in how missing Indigenous people reports are handled,” Squally said. “Throughout history and to this day, tribal people were treated as disposable. Deaths, murders and disappearances were ignored in every way.”

Squally pointed to the recent discoveries of thousands of children in unmarked graves at boarding schools as disturbing evidence of a lack of regard for tribal people.

“Having an alert system for our people will help jump the slow reporting time that too often means our people are never found,” Squally said. “It’s a crucial piece in improving the chances of finding our loved ones.”

Squally hopes the notification and associated photos of the missing people will work to prevent the disappearance or killing of Indigenous people. She pointed to a March 15 incident when Nisqually tribal member Aaron Squally — who had been missing for a week — was found murdered in the area.

“It is early in his murder investigation, but we are praying for his justice, praying for closure for Aaron’s dad, sons, grandchildren, and the rest of the family,” Squally said. “It is heartbreaking losing a family member in this way. The tribe plans to meet with our U.S. attorney and bring this issue to his attention and express some concerns with the current process of handling these matters.”

The true number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the United States is unknown because of reporting problems, issues with jurisdictions and law enforcement not responding to inquiries.

“The cops would say they were runaways or they just left without informing anyone,” Squally said. “We knew it wasn’t the case. Our people kept vanishing and nobody batted an eye. We’d have two weeks of investigating, if that, then nothing. It has been up to the families to hire private investigators to help find their family members and it’s still that way sometimes.”

According to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), Indigenous women face murder rates almost three times as high as white women and up to 10 times that of white women in some locations. More than 80% of Indigenous women have experienced violence, according to NCAI.

“This has been an issue since the first coming of settlers,” Squally said. “Can you imagine having historic injustice overlooked for so long and just now receiving this kind of attention? Just in my 29 years here, there’s been many Indigenous people, a lot of which are my family and friends, who have gone missing.”

The Nisqually Indian Tribe has collaborated with other tribes in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People movement by joining Zoom calls or attending in-person rallies.

“There were many meetings, calls and work sessions behind this movement between the 29 tribes and the state of Washington,” Squally said. “Debra Lekanoff, the first native woman in the Washington State Legislature, has hit the ground running since her appointment.”

Last year, Squally spoke on behalf of one of Lekanoff’s bills as she testified on the importance of removing derogatory Native American mascots from public schools in Washington, something the Legislature approved.

“Deb is a consultant for our tribe and an honor to work with,” Squally said.

Along with better communication when someone goes missing, the alert system will allow law enforcement to flag cases for other agencies, allowing them to make better connections.

The Washington State Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force has also formed to coordinate a statewide response and will issue its first report in August.

“We never gave up hope for our missing people,” Squally said. “To my uncle Jerry, I miss you. To my best friend’s sister Kaylee, you were taken too soon, and to my cousin Aaron, we believe and will pursue justice for you.”